- Home

- Giles Tremlett

Isabella of Castile

Isabella of Castile Read online

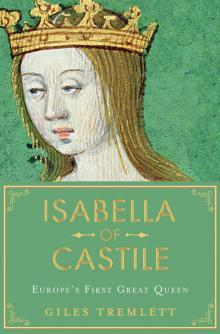

ISABELLA OF CASTILE

To Katharine Blanca Scott, for all we have done and made.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Ghosts of Spain

Catherine of Aragon

ISABELLA OF CASTILE

Europe’s First Great Queen

Giles Tremlett

CONTENTS

Maps

Family Tree

Introduction: Europe’s First Great Queen

1No Man Ever Held Such Power

2The Impotent

3The Queen’s Daughter

4Two Kings, Two Brothers

5Bulls

6Choosing Ferdinand

7Marrying Ferdinand

8Rebel Princess

9The Borgias

10Queen

11And King!

12Clouds of War

13Under Attack

14Though I Am Just a Woman

15The Turning Point

16Degrading the Grandees

17Rough Justice

18Adiós Beltraneja

19The Inquisition – Populism and Purity

20Crusade

21They Smote Us Town by Town

22God Save King Boabdil!

23The Tudors

24Granada Falls

25Handover

26Expulsion of the Jews

27The Vale of Tears

28The Race to Asia

29Partying Women

30A Hellish Night

31A New World

32Indians, Parrots and Hammocks

33Dividing Up the World

34A New Continent

35Borgia Weddings

36All the Thrones of Europe

37Though We Are Clerics … We Are Still Flesh and Blood

38Juana’s Fleet

39Twice Married, But a Virgin When She Died

40The Third Knife-Thrust of Pain

41The Dirty Tiber

42We Germans Call Them Rats

43The End of Islam?

44The Sultan of Egypt

45Like a Wild Lioness

46The Final Judgement

Afterword: A Beam of Glory

Appendix: Monetary Values and Coinage

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Plate Section

‘No woman in history has exceeded her achievement.’

Hugh Thomas, Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire

‘Probably the most important person in our history.’

Manuel Fernández Álvarez, Isabel la Católica

INTRODUCTION

Europe’s First Great Queen

Segovia, 13 December 1474

The sight was shocking. Gutierre de Cárdenas walked solemnly down the chilly, windswept streets of Segovia, the royal sword held firmly in front of him with its point towards the ground. Behind him came a new monarch, a twenty-three-year-old woman of short-to-middling height with light auburn hair and green-blue eyes whose air of authority was accentuated by the menace of Cárdenas’s weapon. This was a symbol of royal power as potent as any crown or sceptre. Those who braved the thin, wintry air of Segovia to watch the procession knew that it signified the young woman’s determination to impart justice, and impose her will, through force. Isabella of Castile’s glittering jewels spoke of regal magnificence, while Cárdenas’s sword threatened violence. Both indicated power and a willingness to exercise it.1

Onlookers were amazed. Isabella’s father and half-brother, the two kings who had ruled fractious Castile for the previous seventy years, were not famed for their use of power. They had let others rule for them. Yet here was a woman, of all things, declaring her determination to govern them herself. ‘Some of those in the crowd muttered that they had never seen such a thing,’ reported one contemporary. The grumblers felt no compunction about challenging the right of a woman to rule over them, and little need to keep their mouths shut. Castile’s weak monarchy had become the subject of derision, disobedience and outright rebellion. For decades the country’s kings had been playthings for a section of those mighty, arrogant, land-owning aristocrats who already referred to themselves as the ‘Grandees’. This woman who claimed to be their new queen on a December day in 1474 may have appeared in her most magnificent, bejewelled finery, but only a modest number of Grandees, churchmen and other senior officials accompanied her. It was a sign that her problems went beyond her gender and the fragile state of Castile’s monarchy. For Isabella was not the only claimant to the throne, nor was she the person who had been designated as such by the previous monarch. This was, in short, a usurper’s pre-emptive coup. Nobody could be sure that it would work.2

Castile was the largest, strongest and most populous kingdom in what the Romans (and their Visigoth heirs) had called Hispania and which today is divided between the two countries of the Iberian peninsula, Spain and Portugal. With upwards of4 million inhabitants it was significantly more populous thanEngland and one of the larger countries in western Europe. The kingdom that Isabella claimed was the result of a slow, six-centuries-long conquest of land occupied by the Muslims – known to Christians as moros, or Moors – who had crossed the nine miles of water that separate Spain from north Africa at the Strait of Gibraltar and swept through Iberia early in the eighth century. Castile’s recent history was less than glorious and its experience of queens regnant was both distant and, by reputation, dismal.3 No one alive could recall what it was like to have a strong monarch, while infighting and troublesome neighbours – Aragon to the east, the Muslim kingdom of Granada to the south and Portugal to the west – continued to absorb much of its energy. Dealing with these three countries and the small but often irritating northern kingdom of Navarre was about all it was able to manage in terms of foreign adventures – though the royal family had often looked abroad for marriage partners and Isabella herself boasted both a Portuguese mother and, in Catherine of Lancaster, an English grandmother. To the north, France remained a far more potent power – one that Castile was careful not to upset.

Those watching Isabella process through the cold streets of Segovia could not know that they were witnessing the first steps of a queen destined to become the most powerful woman Europe had seen since Roman times. ‘This queen of Spain, called Isabella, has had no equal on this earth for 500 years,’ one awestruck visitor from northern Europe would eventually proclaim, admiring the fear and loyalty she provoked among the lowliest of Castilians and the mightiest of Grandees.4 This was not hyperbole. Europe had limited experience of queens regnant, and even less of successful ones. Few of those who followed Isabella have had such a lasting impact. Only Elizabeth I of England, Archduchess María Theresa of Austria, Russia’s Catherine the Great (outshining a formidable predecessor, the Empress Elizabeth) and Britain’s Queen Victoria can rival her, each in their own era. All faced the challenges of being a female ruler in an otherwise overwhelmingly male-dominated world and all had long, transformative reigns, leaving legacies that would be felt for centuries. Only Isabella did this by leading a country as it emerged from the troubled late middle ages, harnessing the ideas and tools of the early Renaissance to start transforming a fractious, ill-disciplined nation into a European powerhouse with a clear-minded and ambitious monarchy at its centre.5 She was, in other words, the first in that still-small club of great European queens. To some she remains the greatest. ‘No woman in history has exceeded her achievement,’ says the historian of Spain, Hugh Thomas.6 This author agrees, at least as far as female European monarchs and their impact on the world is concerned.

Isabella’s achievements are not just remarkable because of her sex, merely more so. Isabella appeared after more than a century of crisis in Europe. In 1346, a force of

besieging Tartars had catapulted the blotchy, plague-ridden bodies of Black Death victims into a Genoese garrison in the Crimea. This forced them into galleys which carried the disease into Europe, or so the Genoese writer Gabriele de’ Mussi claimed after watching the plague devastate his home town of Piacenza. In fact, the Black Death took many other routes into Europe, where it killed a third of the population. This accelerated the demise of the feudal system in much of western Europe, starving it of manpower and provoking everything from peasants’ revolts to the abandonment of productive land.7 Then in 1453, the handsome, dashing, twenty-year-old Ottoman sultan Mehmet II ordered that his galleys be pulled overland into the Golden Horn, cutting off the capital of eastern Christendom, Constantinople. This soon fell into his hands. Muslim armies then completed their occupation of Greece and much of the Balkans, marking a new low point in the history of western, Christian Europe. The explanation for all this, in a world dominated by religion and superstition, was simple and widely shared. God was angry. His wrath had fallen on a sinful world and, in some parts, it was believed that he had slammed shut the door to heaven. Christians had long dreamed of a mythical, redeeming leader, the Last World Emperor or Lion King, who would recover Jerusalem and convert the world to the true faith.8 Now, with Islam on the rise and themselves faced with apparently irreversible decline, they needed such a leader even more urgently.

Castilians hoped that the great saviour of Christianity would be one of their own monarchs, but weak kings brought constant disappointment. Foreigners saw squabbling Spain as shrouded in ‘natural darkness’,9 and Castile remained a volatile, unsettled society. A whole new social category, the ‘new Christians’ or conversos, was still being assimilated amid frequent outbursts of violence. The conversos were the children and grandchildren of what had once been the world’s largest community of Jews, most of whom appear to have been forcibly converted eighty years earlier. In the cities a growing bourgeoisie of wool traders, bankers, merchants and local oligarchs struggled to assert itself. Elsewhere many strived to attain or maintain the privileges of class – often personified by the broad, if sometimes impoverished, category of hidalgos, whose name derived from the term hijos de algo, or ‘sons-of-something’.10 But real power still lay in the vast, untaxed estates of Grandees, military orders and the church – which were also the biggest threat to royal authority.11 Yet in a continent split into dozens of quarrelsome kingdoms, city states, principalities and duchies, Castile was one of the few countries with the potential to produce a leader who could reverse the flagging fortunes of western Christendom. Vast flocks of hardy, fine-hairedmerino sheep – some 5 million animals – had turned it into whatone historian called ‘the Australia of the Middle Ages’, with wool travelling north to the sophisticated textile centres of Europe.12 In Rome, the spiritual capital of Europe, the pope was only too aware of the importance of this wealth since Iberia provided a third of the papacy’s income.

No one had ever imagined that the Last World Emperor would be a woman, but Isabella, in alliance with her husband King Ferdinand of Aragon, did more than any other monarch of her time to reverse Christendom’s decline. Despite this, appreciation of Isabella has remained a largely Spanish thing. There are many reasons why. One is her use of violence. This is a legitimate and necessary tool for exercising power, but is often deemed disturbing when used by queens – as if those who usurp the male role of leadership are driven by dark and vicious forces that annul a supposedly natural, gentle femininity. Isabella had no qualms about employing violence, feeling the hand of God behind every blow delivered in her name. Nowhere was this more so than in her attempt to finish off the so-called Reconquista by defeating the ancient Muslim kingdom of Granada. Isabella admired Joan of Arc, but made no attempt to imitate her by leading troops into battle. That was man’s work, and she believed firmly in the division of the sexes (and classes, faiths and ethnic groups). In that, and many other things, she was not just a woman of her time, but a ferociously conservative one. Nor did she feel it necessary to feign any form of masculinity, though men often found they could explain her extraordinary success only by attributing to her some of their own, male qualities. Where Elizabeth I would later proclaim herself to have ‘the heart and stomach of a king’, Isabella preferred to express angry astonishment that ‘as a weak woman’ she was so much more audacious and belligerent than the men who served her.

The Castile she claimed the right to rule owed its name to the castles, or castillos, that dotted a kingdom carved out over centuries of warfare and conquest of Muslim lands. Her country’s self-identity was shaped around its role as a crusading nation and defender of Christianity’s southern frontier. The distinct regions of Castile owed their existence, too, to the different stages of a Reconquista which had started in the mountains that loomed over the Cantabrian coast in the north, and spread slowly into the wider area known as Old Castile. This lay north of a central chain of snow-capped mountains and sierras that included both the Guadarrama and Gredos ranges. Old Castile (together with the lands where the Reconquista was launched and had its first successes, in Asturias, the Basque country and Galicia) was fringed to the north and west by a wild, dangerous coastline. It included Spain’s own Land’s End, or Finisterre, where wonderstruck Romans had come to marvel at the sun sinking below the western edge of the known world. This most ancient section of her realms was structured around a network of handsome, walled cities like Segovia, Avila, Burgos and Valladolid that had grown wealthy on the back of the wool trade. Every autumn the flocks of sheep traipsed south across the mountains – or ‘over the passes’ as Isabella herself put it – to their winter pastures in the area that had become known as New Castile. This was presided over by ancient Toledo, with its magnificent churches, converted mosques and synagogues that jointly symbolised centuries of religious coexistence in Spain. Further to the south and west lay booming Andalusia, with its fertile plains, Atlantic ports and the country’s biggest city Seville as its thriving capital. Far off to the east lay the thinly populated frontier land of Murcia, which provided Castile with ports on the Mediterranean. Extremadura, on Castile’s western border with Portugal, also owed much of its character to its own frontier status.

Across the varied and often rugged landscapes of Castile – from the green, damp north-west to the arid, desert-like south-east – Isabella’s violence was directed against those who opposed her usurper’s coup, challenged royal authority or threatened the purity of her kingdom. Religious and ethnic cleansing saw thousands burned, tens of thousands expelled13 and many more forcibly converted to Christianity. Jews and Muslims were erased from the official population of Spain, forcing many to hide their real faith. Her novel, royal-directed state Inquisition used flimsy evidence or confessions extracted under torture to burn conversos whose racial impurity was often the only real basis for suspicion about their beliefs. And it was during her reign that Christian Spaniards with a Jewish bloodline began to find themselves formally categorised as second-rate subjects. These are terrible acts by the morals of today, but were widely applauded in a Europe which looked scornfully upon Spain’s mix of religions. Many wondered why it had waited so long to do what they themselves had done centuries before.

Religious or ethnic cleansing, enslavement and intolerance were not frowned upon. They could, in fact, be virtuous. Yet even by the measures of her own era Isabella was deemed severe. Machiavelli himself commented on the ‘pious cruelty’14 practised in her kingdoms. In public she perfected a distant form of impassive regality, but behind this lay a woman of intense and stubborn convictions. Only Ferdinand and the handful of stern, austere Christian friars to whom she turned for moral guidance seemed capable of changing her mind. And yet many people were grateful, for that same single-minded severity brought stability and security to their daily lives – shielding them from the violence of mobs, the greed of the Grandees and the casual cruelty of those who rode roughshod over Castile’s laws.

Isabella’s calm exterior hid

not just a strong will but also an elevated idea of her place in history and a desire for lasting fame that drove her ambition far beyond the traditional frontiers of Castile. Ships from neighbouring Portugal were already nosing their way deep into the Atlantic and south down the coast of Africa. Under her leadership, with the help of the talented and eccentric Genoese sailor Christopher Columbus, Castile would push further and deeper west, discovering an entire ‘New World’ that won it glory, power and gold. This also wrought a fourfold increase in the geographical size of what would eventually be termed ‘Western civilisation’ and helped provoke a tectonic shift in global power. It was, in many ways, the miracle for which embattled Christendom had been waiting.

All this was achieved, in part, because Isabella began the process of imposing what other princes and monarchs across Europe were also battling to install – a new kind of royal dominance that reduced the political power of feudal lords and handed more to a new class of loyal and dependent royal bureaucrats. It was a bold, clever transition, not revolutionary but still profoundly transformative, and all done by appealing, ironically, to tradition. In her desire to draw as much power as possible to the crown – a precursor to the absolutist monarchies of later centuries – she saw eye to eye with her husband Ferdinand, whose lesser kingdoms of Aragon eventually gave them joint control of most of contemporary Spain, though this kind of rule was much easier to implant in Castile. Indeed, her greatest political act was to forge an alliance with Ferdinand that was at once unique and clearly understood by both, though it provoked – and continues to provoke – confusion. ‘Some people may be astonished, and say, “How! Are there two monarchs in Castile?”’ asked one befuddled visitor from England, writing in French.15 ‘I write “monarchs” because the king is king on account of the queen, by right of marriage, and because they jointly term themselves “monarchs”.’ Even contemporary observers, then, struggled to understand this unique phenomenon, with wilder explanations painting the queen either as a silent and subservient companion to Ferdinand or, alternatively, as a man-dominating harridan. Yet the royal ‘we’ employed in their letters reflected reality, for Isabella’s signature was also her husband’s, and vice versa – at least in Castile, for Aragon’s laws made her queen consort and, in practice, the junior partner there.

Ghosts of Spain

Ghosts of Spain Isabella of Castile

Isabella of Castile